Why Taxis Were Invented

Flew to Mexico City for a week-long visit with only two goals: meet a friend and return home in one piece. Arriving in the evening, I discovered my cell phone failed to find a signal (guess I forgot to figure that out), but the airport internet service allowed me to email my friend, BR, who was waiting in a different terminal. For fifteen years I had known him, yet we never met in person. Over this time (over the Internet), he proved himself to be a thoughtful, honest man who worked hard, harder than I, translating a gigantic medical book. So it seemed fitting to meet him as a friend, now that I had ended the employment that brought us together.

BR is a medical doctor turned translator. He’s a smart man, often correcting problems in the English text, usually medical inaccuracies but also some grammar.

As BR drove us away from the airport, I thought, “How nice to soon be at the hotel,” it being late in the evening. After ten minutes of driving, I noticed we were passing once again the row of car rental places. His smart phone, with its GPS, had died. BR was manifestly better at following a medical text in a foreign language than at following the road to Central (downtown) Mexico City.

Pulling out my laptop, I began charging his phone, which came alive with its GPS signal. All set. ¿No? Every few blocks a turn would be announced, we’d miss the turn, and “Urrzzt” the phone would hiss, letting us know it was finding new directions.

Finally we nearly made a turn as called for by the GPS. It was U-turn onto a busy road, except that as we were half-way through the turn, two lanes of cars were flying toward us. They were coming for my side of the car. The relief at nearly making the turn on time, coupled with the anxiety of impending death, put me into a spasm of laughter, nearly uncontrollably. The situation forced us to take the turn wide, finding ourselves alive but on a side road leading through some desolate blocks of dusty, broken concrete roads, surrounded by dark buildings in obvious decline. “Urzzttttt.”

This is why taxis were invented.

Teotihuacan

The rest of my time in Mexico we traveled by taxi and bus, the buses having always been part of the plan.

Our only archeological outing was to Teotihuacan. A native name adopted by the Spanish, it is now pronounced roughly “Tow-tea-wa-`can”—with the accent on the final syllable. According to Wikipedia, Teotihuacan was the name “given by the Nahuatl-speaking Aztecs centuries after the fall of the city around 550 A.D.” This civilization itself was contemporary to the Mayans and preceded the Aztecs. Teotihuacan was the first metropolis of North America, growing to around 250,000 inhabitants at its peak.

Through Teotihuacan, one of the oldest pyramid locations and the most popular archeological site in Mexico, we were accompanied by a guide, Javier. Here the guide and I are in the area called Ciudadela, climbing steps toward the Temple of Quetzalcoatl:

Quetzalcoatl was a primary god to whom humans were sacrificed. Myth had it that he would one day return, and when Montezuma heard that Cortés had landed (1519), he thought it was Quetzalcoatl returning, which, measured by the ongoing-need for human sacrifices, it truly was.

I pressed Javier on the issue of human sacrifice (among the Teotihuacanos), which he said occurred as an honor for the virgins so sacrificed. Other sources, though, say the victims were often enemy warriors, and that often the sacrifice was coupled with the dedication of a new building. At any rate, there was plenty of premature death to go around. Javier explained the sacrifice simply: “You see, the Teotihuacanos were very religious and therefore sacrificed humans.”

One might think the equation with religion and human sacrifice is simplistic and reductive (of religion). I did as he spoke. However, I was arguing with my better self. Primitive religions have more sacrifice in their development than one may expect or wish to discover.

So, as we walked away from Quetzalcoatl toward the Pyramid of the Sun, I began to appreciate the equation between religion and sacrifice. What I had noticed in the Temple of Quetzalcoatl, as well as later in the museum (built near the Sun), was that it wasn’t the human sacrifice that received descriptive attention, but the relics and symbols that grew up around the sacrifice, providing additional meaning to the culture. The impulse to make the sacrifice significant, if not altogether super-natural, is tremendously powerful. Here, behind BR and myself, are some of the carvings toward the base of the Temple of Quetzalcoatl:

The myths of animal-like deities and human-like deities populated the world, adorning the stones, and—one assumes—the minds of the inhabitants with a highly complex and varied set of meanings.

Perhaps not only the victims, but the community (which grew to ~250,000 people by AD 450), supplied enough bodies to fill the Avenue of the Dead, the long road from the temple (where sacrifices occurred) to the Pyramid of the Sun, and that of the Moon. Javier and I walk along the Avenue, with the Pyramid of the Sun clearly to the right and thePyramid of the Mood straight ahead of us, distantly:

Our guide, who spent all day, every day, climbing the multitudinous stairs of Teotihuacan, turned back as we continued our tour by climbing the 240 or so stairs up the Pyramid of the Sun, which stands impressively high even though it was probably higher back in its time. Here’s the ascent:

Here’s the descent:

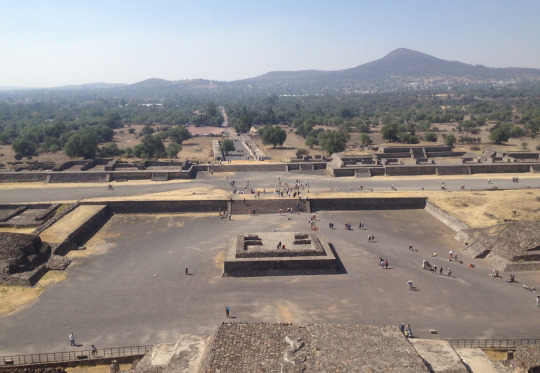

From the top, one can see the valley, the claim being that only the “downtown” buildings survive, but that the inhabitants, in their less durable dwellings, extended beyond the mountain in the distance:

The Road

Veracruz (both a state and a city) is where BR lived during some important years of his childhood and is where he hopes to live again, now that his children are adults. So we planned a trip there.

In order to go swimming in the ocean, something BR knew wasn’t recommended in the polluted waters of Veracruz, the city, we first took a bus north of Veracruz toward Nautla, where a small resort provided access to the beach, along with a dirt road on which to run, and a restaurant (from which to watch the Super Bowl in Spanish, without the glitzy US commercials, as it turned out):

Veracruz

Veracruz, the True Cross, was named so by Cortés, who landed there on Good Friday. BR had a short list of places to visit in Veracruz, which was currently under the sway of Carnival, causing some places and roads to be closed in order to manage the crowds.

The first evening, we ate dinner at “Grand Cafe de la Parroquia,” where, to make foam in your cafe au lait, the waiters skillfully hold poured the milk from a great height into your glass:

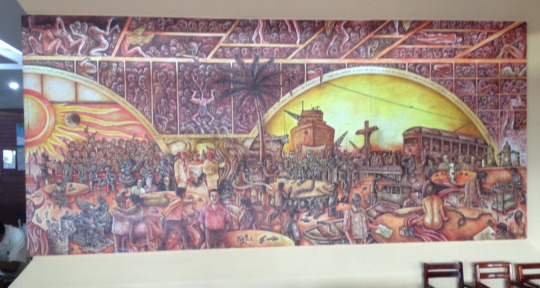

If one walks around the Parroquia, one can see artwork, including a large mural that brings together the culture of Veracruz, present and past phases, including virgins for human sacrifice:

Afterward, in a taxi, BR asked the important questions of the driver. The questions involved the short list of things that had made him love the city: can you take us where the flamingos live? to the park? to the beach? Not following the Spanish, I had to wait for BR to explain the conversation that followed between him and the taxi driver.

The driver’s replies went something like this: How about I take you to a table dance? (No table, no dance, said BR, only flamingoes.) Well, how about to a regular bar? (No bar, said BR, only the park.) The park was gone, the flamingoes gone, the beach was closed (for Carnival). The driver then summed up the Veracruz that BR and I were visiting: “Veracruz has become the longest bar in Mexico, a 40-kilometer bar!” Perhaps this description was more apt during Carnival but it became a catch phrase between BR and myself, “the longest bar in Mexico.”

So we had the taxi drive us to an old church, Iglesia del Cristo, that was closed. At this point BR quoted Victor Hugo: “The difference between the door of a priest and the door of a physician is that the door of the priest should always be open, and the door of the physician should never be closed.”

So there we were, witnessing the changes in Veracruz over the years. Not all was lost, though. The brown bag (above) in BR’s hand—it contains some bread we had found at a bakery. “Chamuco” is a special sweet bread, specific to Veracruz, that persisted from BR’s childhood through his later visits even to this evening!

Whether or not the city of Veracruz is becoming a 40-kilometer bar, it also is filled with “los jarochos” the people (and music) of Veracruz, a happier people by and large than those in Mexico City, and distinguishable by their demeanor if not their accent (obvious to BR and undetectable to me). More obvious to my ears is the pre-Ritchie-Valens version of the song “La Bamba,” which originated in—and expresses the happiness of—Jarocho art, combining Spanish, native, and African elements.

Finally, we went to the home where BR lived as an adolescent. Now a graphics arts studio, at least it was still there on Vicente Guerrero (avenue). An elderly man and a middle aged woman were on the steps of the building next door. BR approached them and asked if they knew Mr. and Mrs. Aguilar, who used to live there. To this the woman said brightened up and exclaimed, “I’m Ana, their daughter. You and I played together … . ” Hugs all around.

Later, BR said, “Who knows? If I had stayed there, we may have married.”