Brief and Tedious Preface

No, I have not recently returned from Peru, though I wish I had. Instead, I’m using some annotated photos from a 2008 trip and am converting them into an entry here. There are several unspeakable reasons for this.

Arriving Cusco

First Few Days

Toward Machu Picchu

Machu Picchu Itself

Pisac / Písac

Leaving Cusco

Arriving Cusco

Cast: three of my four daughters (who spoke much Spanish and a little Quechua), and myself, who joined later (who spoke a little German, less Spanish, and had not heard the name of the native language).

Where we were: Cusco (Cuzco), plus parts of the Sacred Valley, which is north-to-northwest of Cusco. The Sacred Valley contains the Urubamba River, many Inca sites, and several towns, including Písac, which is mentioned later (click most images for enlargement).

First Few Days

Learning to fly . . . : Flying into Cusco means landing at about 11,000 feet, not a feat to be taken lightly. My pilot did not take it lightly, I was convinced, when mid-morning he circled cloudy Cusco about six times and returned straightway to Lima until the next day.

Most of the outlying Inca sites, including Machu Picchu, are lower in altitude than Cusco itself.

So, that cloudy day my two guides, Sarah and Laura, waited wonderingly, if not also patiently.

Soon we took a bus to the Sacred Valley and hiked above the Tambomachy ruins.

New day. New ride on a bus to the Sacred Valley to a highway junction, where a taxi driver took us the rest of the way on a dirt road toward Maras, Peru. Unforgettable are the salt mines that are older than the Incas and blend into the mountainside so well.

In the town of Maras, children find a way for fun on, I think, a sheet of cardboard, or their mother hopes so (click image for animation):

Toward Machu Picchu

Two of my daughters, Sarah and Laura, had been traveling and camping in South America for months before I arrived. Their sister Amy was soon to arrive in order to attend a Spanish school in Cusco (living with a host family).

When I arrived in Cusco, Laura and Sarah thoughtfully upgraded from a hostel that was 10 soles a night to one that was 15 soles (about US$5). They found a way to do everything at practically no cost with the result that they saw genuine, unvarnished people and places in those countries. Some were so unvarnished that their lives were in danger at times, but that would be a matter for a different travel log.

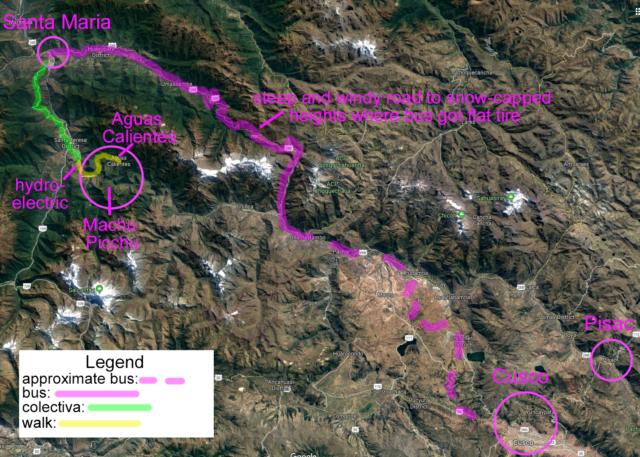

In keeping with frugality, our trip to Machu Picchu bypassed the train ($ the obvious route $) and took the route less traveled. Only later did I read several web pages that advised against our route for matters of safety and convenience—and yet it was one of the most memorable parts of the entire trip. It took us high into the Andes in a bus and then down to the jungle to a town called Santa Maria. (We had been joined by Amy by this time.) If the trip away from Cusco was exciting, the return trip was more so, when the bus tire was burst by a large rock on a sharp corner. The entire extended family (for I think the bus was a family business) got out in the rain and pitched in to replace the tire.

From Santa Maria, we boarded a Toyota van called a “colectiva” that held about 3x times the recommended capacity. The capacity was increased both by removing some seats and by including people on the roof (not necessarily with the permission of the driver).

The colectiva whisked us along a narrow dirt road that edged its way up the side of a mountain.

Once the driver got out and wrestled with the woman. She dumped a whole bucket on his head. We heard that they are married.

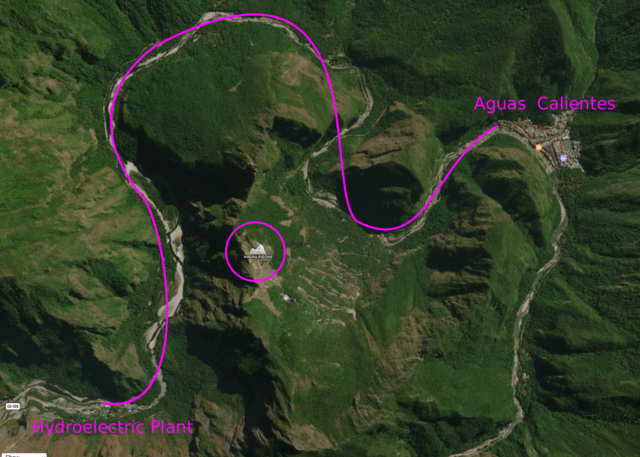

The colectiva dropped us off just past Santa Teresa at the hydroelectric plant on the Urubamba River. From there we walked the ~7 miles to Aguas Calientes, the town just below Machu Picchu.[1]

Machu Picchu Itself

Many people believe that certain places have sacred or unique spiritual value (with, say, cemeteries at one end of the spectrum and temples, ancient or new, at the other end). At times, I wish I believed that too. If nothing else, the belief enhances the sightseeing enterprise, howsoever self-contradictory that sentiment might be, since sightseeing has undertones of consumerism when done mechanically or for what is popularly called (with a mechanical metaphor) “the bucket list.”

For me, my mind is in the gutter when it comes to spiritual value, but not perhaps in the way you think. A spiritual moment, being a moment when the finite being reaches out by faith to the too-big-to-be-seen creator, involves humility and trust, a trust that wherever I am, I am in the creator’s heart, whether it be a gutter or the mossy rock looming above the Inca ruins. In other words, spiritual places involve attitudes, not altitudes.

That said, it’s time to see the sacred place (briefly, since it’s so well documented by others).

If the Inca ruins did not exist, Machu Picchu would retain much of its attraction, because of the steep, deep green, misty if not mystical peaks that surround it.

Traveling to the Peruvian Andes in January entails affordable airfare and the possibility of rain. It rained for hours while we slept in Aguas Calientes, and only occasionally as we hiked that day.

On the descent from Wayna Pikchu, Sarah and Laura talked us into going to the Temple of the Moon, named by an early manager of the Machu Picchu hotel. It is a place probably unrelated to the (persisting) Inca interest in the moon. The ruins are impressive if one can breathe at that point in the hike.

Sarah and Laura wandered off and caught an impressive view of Machu Picchu. This place—this hidden civilization—was likely an estate for the Inca emperor Pachacuti, abandoned, and kept secret until Hiram Bingham discovered it in 1911.

Views such as this were afforded by the point to which Laura and Sarah climbed.

While Amy overlooked the Temple of the Moon.

A lightly annotated version.

Moving toward the southern end of the saddle, one can view the Inca drawbridge, whose protective function is self-evident.

A parting shot of Machu Picchu. Perhaps we cared more about the periphery than the center, or more about the natural beauty than the highly trafficked spots, not that I wouldn’t be glad to return and spend a few days learning the place.

We spent a 2nd night in our Aguas Calientes hostel, and in the morning, hiked to the hydroelectric plant. There we got in a colectiva that ultimately held about 22 people and 2 on the roof. It was a long, beautiful trip, and when we arrived in Santa Maria (pictured below), I said, “I just need to urinate before we get in the bus,” but as soon as we got out of the colectiva, we were ushered onto a bus that we were told had a toilet (whose door that hadn’t been opened for about 5 years).

After about a half hour, the driver stopped the bus to let Sarah and me get off and relieve ourselves. Being in the back of the bus, I was slow to get off and to get back on. While I was trying to nonchalantly make water with my back turned to an overloaded bus full of people, the driver decided to start driving. Sarah had made it back on. As I’m told, the whole bus load of people began to plead with the driver, “do not leave the father.” I ran up the road about 100 feet and got back on.

Later, when it was getting dark, our bus went through a place where the rain had caused a landslide, and a (very) large rock blew out one of the tires on the bus. This photo is very close to what you would have seen if you looked down upon us after the blowout.

We finally got going again and made it home around 11PM.

Pisac / Písac

It is Písac, a medieval town adjacent to Inca ruins (Inca Písac), that I loved most. This area is as beautiful as Machu Picchu, yet different, and not nearly as highly trafficked.

Perhaps my love is the love one holds for the runner-up or the ones who also ran. I don’t know that Inca buildings were ever a competition, but if they were, I can imagine the stone worker boasting, “My pieces fit so well… they fit so well that when an earthquake comes in two hundred years, the Spanish buildings will fall but mine shall remain” (which was the case in 1650 in Cusco).

In my next travel log I explain more about the approach to—and charm of— Písac. For this initial visit our attention was on the ruins, so we quickly made it through Písac to the far end of the ruins in order to be able to walk through them, arriving back in Písac at the end.

Whereas Machu Picchu sits at about 8,000 feet, Písac is higher. The town stands at almost 10,000 feet. The ruins, rising nearly 11,000 feet, are frequented by wispy clouds.

A fellow named Miguel offered to be our guide, we declined, and then he hiked with us, guiding us anyway.

I asked Miguel, our guide-buddy, if the Incas used to sacrifice people. “No, he said. Usually llamas. Sometimes women.” (For a guy obviously happy to be with two North American women, that was quite a statement—not sure he knew how close he had just come to being a human sacrifice himself.) Slaves also entered into that number of victims, and as with many ancient civilizations, it was an honor to be chosen for the gods.

As I close this section, I am a little sheepish, talking of love for the place at the beginning and ending with only occasional sketches. Ah, well. Perhaps I’m due for another (circumspect) visit!

Leaving Cusco

Back in Cusco, we drank matte on the roof of our hostel, with its beautiful nighttime view, slept, walked down the very steep and narrow roads leading toward the plaza, ate a breakfast at a non-profit place that knew how to appeal to northern appetites, and put me in a taxi.

It was a sweet place (and obviously geared for children, the salt & pepper shakers being just an example).

_________________Footnotes_________________

[1]Aguas Calientes has since been named “Machu Picchu Pueblo,” with mixed reception, one problem being the false assumption by first-time visitors that the train will take them directly to Machu Picchu, while it actually will drop them off a couple of miles away in Aguas Calientes.