One would think that someone who had both taught Shakespeare and written a dissertation on the Globe playhouse would have made an early visit to England to know what he was talking about. Not I. Instead I waited about 25 years to visit, and not for a professional reason, but for the opportunity to visit Chris, a friend from my undergraduate days, and Adrienne, his wife.

Chris is one of those rare people who have the ability to “speak the truth in love,” as if he can both see something troubling in a person and still see the person. In other words, my blind spots do not create his own blind spots (and this observation refers mostly to our undergraduate days, if, as I hope, the blind spots are diminishing).

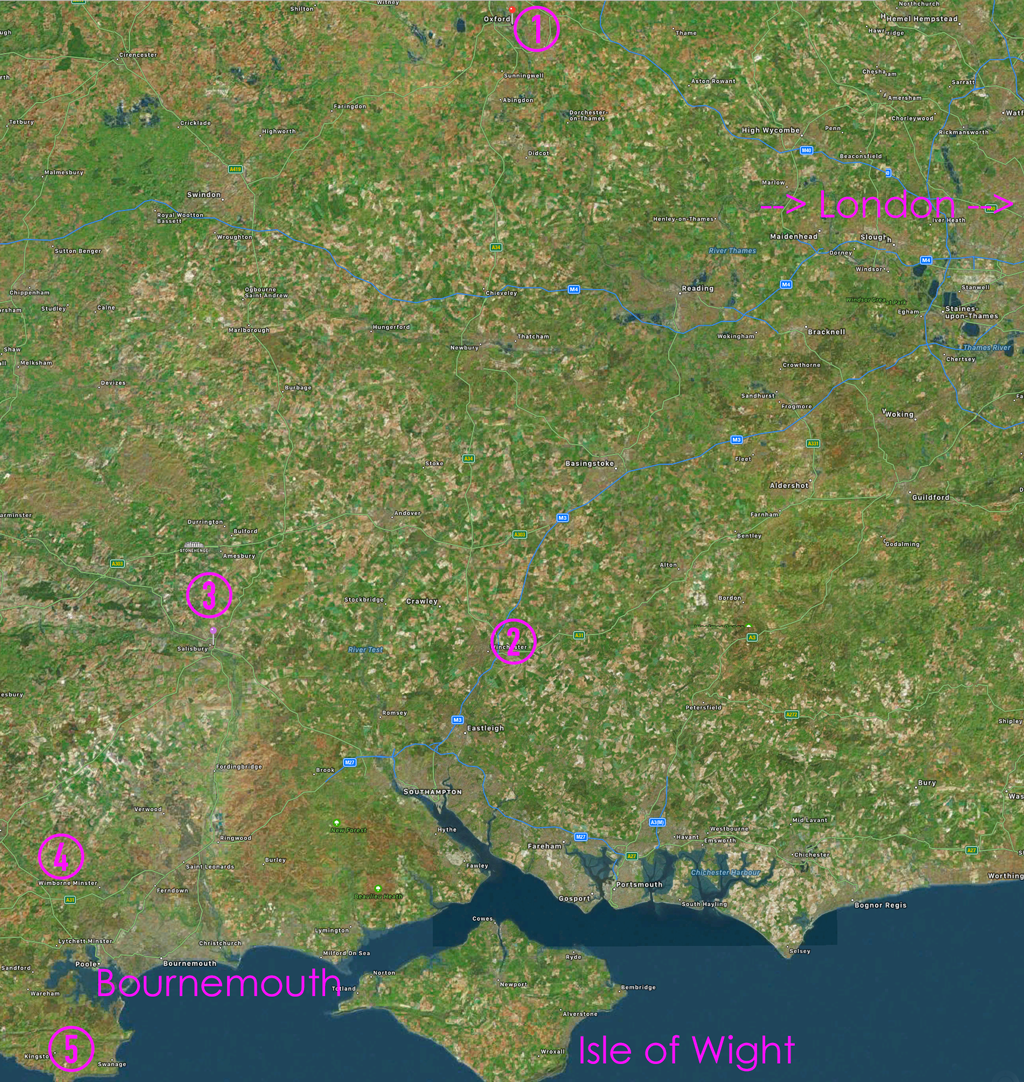

(What follows is a map of the places we visited, leading to an in depth description of the places—basically a travelog that could save you a journey to Southern England or, may I humbly suggest, make your journey richer.)

Adrienne carries on domestic duties in a conventional way while Chris is raking in the money teaching English. Both of course could imagine spending their time differently, but the arrangement apparently suits them both. While Adrienne is good at being flexible, she could, if pushed too far, trounce a person…it was something about the way she swims in the English Channel year round without a wet suit or drinks apple cider vinegar, garnished with crushed egg shells, that earned that recognition. She sometimes teaches at the English school, gardens there and at home, and, as she calls her wanderings through nature, “forages” whenever possible. Not wanting to disrupt the obvious balance of their lives, I behaved my best while in Southern England, staying at their home in Bournemouth when we were not driving or biking to various sites, mostly historical or, better, those that combine something ancient with natural beauty.

English Channel, Bournemouth – looking toward Purbeck

Part of Chris’ job is being a tour guide to his students who come from around the world and have an interest in learning England as well as English. A trip to Oxford University, Chris has found, is about as far as a day trip should be, and that was as far north as we strayed. One way (motor vehicle) or another (bicycle), we had five outings, listed approximately from north to south:

(1) Oxford (2) Winchester

(3) Downton | Stonehenge | Old Sarum | Salisbury

(4) Wimborne Minster

(5) Isle of Purbeck | Corfe Castle | Wareham

Oxford

Oxford University, like Hamlet and the Grand Canyon, is so familiar to me through reading and photos that I cannot separate what I saw recently from what I expected to see, and at the same time I admit a truly superficial knowledge of the place and its traditions. It’s hard to imagine spending one’s time studying in a place like the college of Christ Church:

On one hand, the ambience seems perfect for a cloistered scholar, while on the other, the pressure of succeeding, coupled with the long leash allotted between exams, could lead some to sabotage the situation.

On one hand, the ambience seems perfect for a cloistered scholar, while on the other, the pressure of succeeding, coupled with the long leash allotted between exams, could lead some to sabotage the situation.

Of special interest to me was Magdalen (“Maudlin”) College, where C.S. Lewis taught for most of his life:

In spite of the beautiful grounds and his noted accomplishments at Magdalen, Lewis wrote to Tolkien, “I am certainly a much, and perhaps an increasingly, hated man”[1]. In the words of a former student of Lewis, “Oxford dons objected to Lewis, not for becoming a Christian, but for advertising the fact. His way of putting intellectual and moral pressure on people in print for the purpose of converting them was an offence against academic etiquette. Unspoken rules of academic decorum required one to be decently secretive about religious convictions.”[2] Within a year, no doubt encouraged in part by these conflicting sentiments, Lewis moved to Cambridge. There he taught at Magdalene (with a final “e”) College, remarking that his new Magdalene at Cambridge was the redeemed and consecrated Mary Magdalene (unlike Oxford’s). It’s a nice ending to the story, except similar prejudice met him in Cambridge, but this time he wore his rejection with a difference: he had been unanimously elected as a full professor, something Oxford had failed to do.

While on the topic of Lewis, let me mention our related stop at The Eagle and Child, the Oxford pub renowned for the meetings of the Inklings, where Lewis, Tolkien, Charles Williams, and others spent time reading their manuscripts aloud:

Inside the pub, a quote from C.S. Lewis appears at least two times, once in chalk and once in paint: “My happiest hours are spent with three or four old friends in old clothes tramping together and putting up in small pubs … .” It surprised me that Lewis’, and not Tolkien’s, was the name most obviously being capitalized upon. No doubt, the “hated man” quote does not appear in the pub, while if I had poked around, I would have uncovered references to Tolkien, making currency of his name, too. The writers did, at any rate, put the pub on the map permanently and unregrettably. It was quite busy by our mid-afternoon visit, our small party finding a cramped table where, in order to shift seats, we spilled only a part of a beer.

One Oxfordian treasure that Chris led us to was a college, Keble, whose grounds and buildings are gloriously maintained. It is, by English standards, relatively new, being Victorian. In an anteroom of the chapel hangs “The Light of the World”—an allegorical painting by William Holman Hunt. The chapel itself, with a student playing the organ, awoke in me a hint of the attachment that many Christians (and others) feel for such chapels and cathedrals.

The cumulative effect of standing in this chapel that day and several others the next week was that I thought, “Here, I could believe in God.” Next, as the thought lingered, I added, “Except I already do believe in God, the God with no boundaries, and I belong to church, the church without walls.” Even then, a peaceful, easy feeling accompanied me beneath those high ceilings built who knows how by men that risked their lives for an ideal and enough food to keep their families fed.

Winchester

To my guide I owe, among many other things, these two facts: (1) to be a city in England, the community must house a cathedral, and (2) “chester” as in “Winchester” refers back to the Roman occupation of England (43-410AD), derived from the word “castrum” for military camp. Accordingly, although Bournemouth has over four times the population of Winchester, it is a town, and Winchester, with its Cathedral, is a city. The military aspect of Winchester presents itself several ways, including through the two medieval gates still standing (Westgate and Kingsgate), as well as a castle and other fortifications.

Most of these buildings originated in the 12th and 13th centuries, many of them having been restored, modified, and expanded up to the present. Below is the outside of the Great Hall:

Inside the doorway (where the person is standing) one can enter the Great Hall (except when it is closed, such as when we showed up, our visit coinciding with a memorial service). Peeking in we could still see what is called King Arthur’s Round Table, hanging high on the wall like a giant archery target, painted alternately white and green. The table dates to the 13th century, placing it much later than Arthur (5th-6th century) and a little later than the Arthurian Legend (12th century). Its current paintwork dates to the 16th century, which the Wikipedia article considers “late” relative to the table itself. The obvious giveaway for the date of the current paintwork is King Henry VIII’s image at the twelve-o’clock position, seated in Arthur’s chair.

Winchester Cathedral dates to the 11th century, remains the longest Gothic cathedral in Europe, and holds the remains of Jane Austen.

What captured my imagination and respect, however, was the bust and story of William Walker:

His fame arose from the fact that, around 1905, it was discovered that the foundation of Winchester Cathedral was degrading quickly. Sitting on several feet of peat, the building was sinking and tipping as the peat was saturated by ground water. From 1906 until 1911, six hours a day, six days a week, Walker put on his clumsy diving suit and descended into the mud, in complete darkness. He would remove boards and peat, replacing the old material with bags of concrete (25,000), concrete blocks (115,000), and bricks (900,000). Once he finished his work, the ground water was safely pumped out and the cathedral sat (and sits) on a solid foundation. One should remember that all this underground work was performed where bodies had been buried for hundreds of years. William relied on a smoke from his pipe every time he emerged in order to disinfect himself. Kudos, William the Conqueror of Faulty Foundations.

The “close,” or the immediate area, surrounding Winchester Cathedral contains other historic buildings that come in quick succession. One passes Winchester College, which, according to Adrienne, is, “the oldest continually running school in Britain. It was built during the black death to give an education to poor scholars. Now it’s for the very rich – about £60,000.00 per year!”

A few yards away lie the ruins for Wolvesey Castle, also known as the “Old Bishop’s Palace” (12th century).

In Shakespeare’s The Tempest Miranda, who has been stranded on the island since infancy, seeing men swimming to shore—the first men she’s ever seen beside her father, Prospero—proclaims, “O brave new world,” to which Prospero replies, “‘Tis new to thee.” So I noticed that this England was a new world to me, and that the older the architecture, the braver and newer the place seemed.

While the Great Hall sits on the high end of High Street, a statue of Alfred the Great (849-899AD) guards the low end of High Street.

Whether it was for defending Britain against the Danes, reviving learning and monastic life, or establishing a code of law, Alfred’s fifty years on earth and twenty-eight as King of Wessex justify that title.

Little do I remember of Beowulf, the 11th century poem that might glance back to Alfred’s reign, albeit indirectly (since Beowulf defends that Danes against Grendel the monster). One relatively trivial line, however, somehow entered and never left me:

Hylde hine þá heaþodéor –hléorbolster onféng

eorles andwlitan

Loosely translated:

The war-bold one [Beowulf] lying down, the pillow received the earl’s head.

It’s memorable because of the active role assigned to the usually passive “pillow”—it receives his head instead of his head touching the pillow. This grammar echoes Christ’s, “upon this rock I will build my church; and the gates of hell shall not prevail against it.” Again, the usually passive “gates” are the agents of the sentence, instruments of offence, not of defense, as though there’s something quite impatient and indiscriminate about hell. Words, as do buildings, transport me to the past, to a world that I couldn’t predict, even though it all already happened.

Downton | Stonehenge | Old Sarum | Salisbury

Having read William Golding’s The Spire (1964), a novel about the building of the spire at Salisbury Cathedral, I told Chris that this was one place I wanted to visit (being generally agnostic about our itinerary). On the way there, we stopped in Downton, about an hour’s drive from Highclere Castle where the television series was shot. Downton’s St. Laurence Church struck me as more of a church and less of a tourist attraction.

Perhaps for that reason, the woman—a church worker who arrived just as we did—admonished us to read the writing above the alter, which we then saw as we entered:

The writing was elegant, but when I realized we had been directed to read the Ten Commandments, I felt knocked back to my teenage years when I was long-haired and untrustworthy. And I wondered just how irascible I still appeared.

As we arrived in Salisbury and headed toward the cathedral, Chris made a last-minute executive decision half-way through one of the many multi-lane, high-speed, clockwise roundabouts and torpedoed us north toward Stonehenge. He was right to take advantage of the sunny weather (not unusual for my visit). Once we arrived, I was fine with Chris’ unconventional yet legal backdoor approach to the ruins. Even if we had paid, we would not have been able to walk right up to the immense stones—although my friend Howard used to climb on them fifty years ago before things got out of hand in that respect.

Just outside Salisbury sits Old Sarum on a hill. Old Sarum was the first Salisbury (“Sarum” being a possible corruption of “Salisbury”). On a hill top, it was protected by large ditches that were dug around it, putting an advancing enemy at serious disadvantage. In the following photograph, the hill on which the castle stood is seen from the ground upon which the old cathedral stood.

(Model of how it used to look)

In 1226, the cathedral was moved to Salisbury (giving the clergy some freedom from the watchful eye of the castle). Along with the cathedral came the Magna Carta, which remains housed in wonderful condition in the Salisbury Cathedral. Here Salisbury Cathedral can be seen from Old Sarum:

The Magna Carta, a major concession from floundering King John to the nobility, clergy, city of London, Welsh, free peasants, and other entities, marks a portentous power shift when the king could no longer ignore the interests of others.[3] It was annulled by the pope the same year, but as soon as King John died the following year, it was reinstated. When King John’s son, Henry III, heir to the throne, came of age, he issued a substantially revised Magna Carta (1225), which became the standard version.

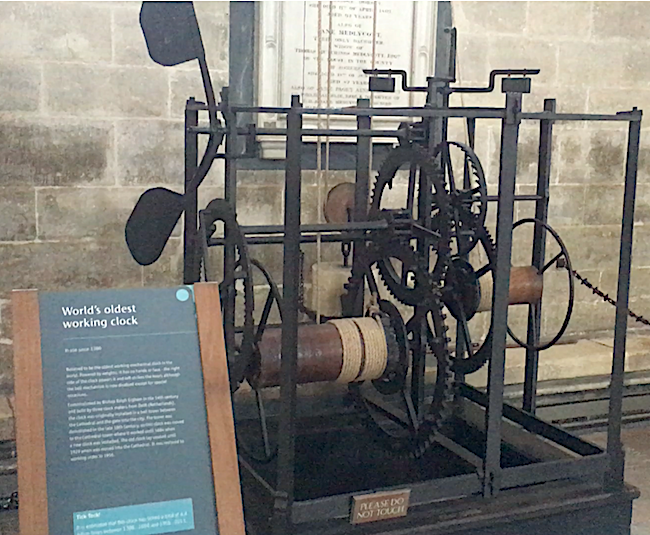

While the Magna Carta alone would merit a visit to the Salisbury Cathedral, so would many other features, including the spire, which was closed to visitors when we arrived, the massive organ pipes, the oldest working clock, and the recent font that is both beautiful and allows full immersion baptism (which is what “baptism” originally meant).

Wimborne Minster

During my stay, Adrienne had been diligently picking up chestnuts from a nearby grove, cross-ing, cooking, and then shelling them. The day we set out for nearby Wimborne Minster, we stopped by some public space for more supplies. It was replete with wild horses (their hoof prints betraying their presence) and apple trees. Chris climbed trees that defied physics in supporting his body weight, all the while chiding me for letting apples fall to the ground instead of heroically diving for each falling apple as though a small bruise would end the world a day sooner.

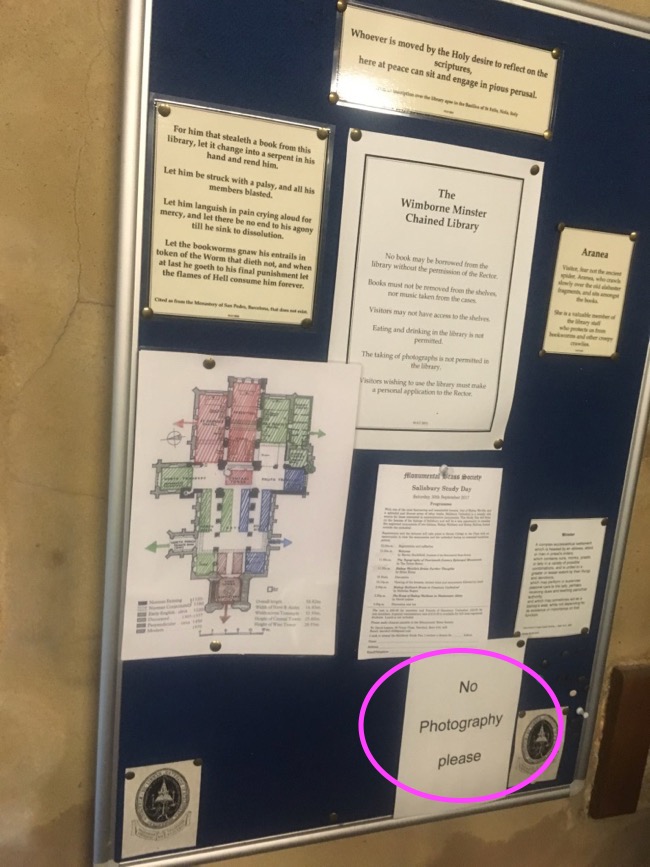

Well, we worked through that apple patch and visited Wimborne Minster, the church. It famously contains one of the few remaining chained libraries in the world. As I recall, the librarian said it was one of four. The definition is slippery.[4] As one can see, the chains—employed to prevent theft of what were truly expensive items when handwritten, as well as at the dawn of the printing press—are affixed to the covers of the books, to prevent damage to the spine. As a result the books are shelved backwards, and only an index allows one to find the desired book without pulling them all from the shelves:

The librarian, speaking to some strangers, also allowed us to handle a few books (not on chains):

She was a tolerant librarian:

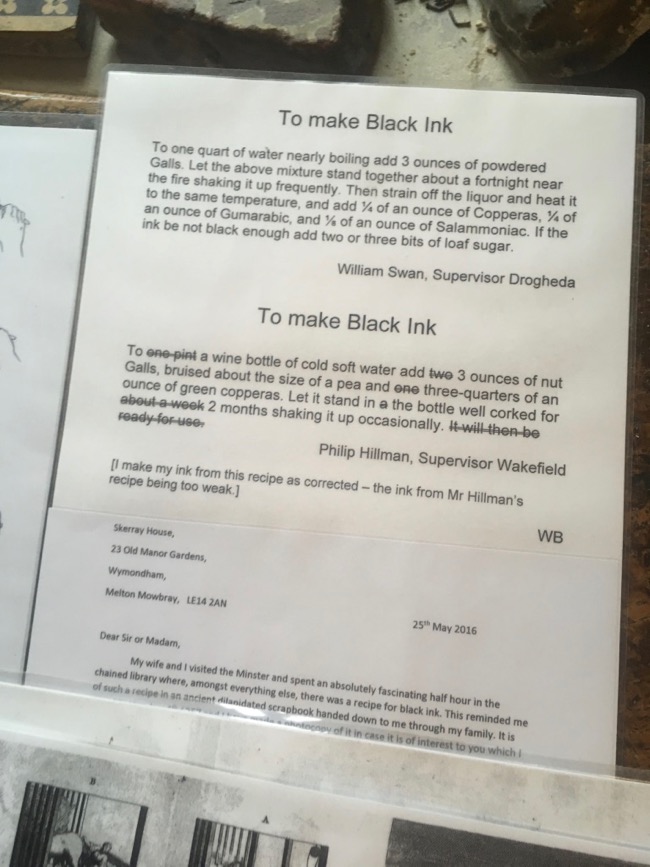

A recipe for the ink that lasts nearly a millennium (to date):

The church itself was characteristically laden with history, including the tomb of the brother of Alfred the Great, as well as the tombs of John Beaufort, 1st Duke of Somerset, and his duchess, the maternal grandparents of King Henry VII. High above the alter hangs an intricate astronomical clock. This photo of the exterior I like in particular because that gentleman could be my late dissertation director, John Murphy, if I didn’t know better:

Kingston Lacy

Afterward we went to Kingston Lacy, an estate that was inhabited by the Bankes family after they, being Royalists in the 17th century, were forced out of Corfe Castle by the Parliamentarians.

The estate included gardens and foxes:

And apple trees that were being trained to grow horizontally…Chris says this is common. I suppose it makes them easier to pick:

We planned to end the outing at Vine Inn, a small pub that Chris knew, although it wasn’t in reality as impressive to Adrienne as it was in his rendition. The bigger problem was that it was closed, but the bathrooms were open (yay):

So we went instead to the Olive Branch, where I learned that the four pounds a friend had given me for the trip were officially obsolete by the end of the weekend in order to make way for the new twelve-sided, harder-to-counterfeit £1 coin.

So we went instead to the Olive Branch, where I learned that the four pounds a friend had given me for the trip were officially obsolete by the end of the weekend in order to make way for the new twelve-sided, harder-to-counterfeit £1 coin.

Isle of Purbeck | Corfe Castle | Wareham

And those pounds, my friend, bring us close to the end. The next day I straightway handed them to Chris in order to pay for the “chained ferry” that would take us and our bikes across Poole Harbour, so that, after a brief stop in a phone booth, we could continue on our bikes toward Corfe Castle.

Probably the highlight of the entire visit, this day involved everything an outing should: a peninsula named “Isle of Purbeck,” sheep, cows, a beautiful ruined castle and a town made out of its stones (those practical Parliamentarians), the nicest chapel by my rustic standards, coffee, beer, and a final shish kabob before a train ride home—a time not unlike “three or four old friends in old clothes tramping together and putting up in small pubs.”

Another view of Corfe Castle:

And another:

Not our train in the distance:

We instead rode our bikes to Wareham. Chris caught this fiery light of the setting sun coming through the windows of St. Martin’s Church:

Eating, we waited for the train:

And that was that. Next morning, I flew home, grateful for one of the best weeks in, as Shakespeare’s John of Gaunt says,

This royal throne of kings, this scepter’d isle,

…

This blessed plot, this earth, this realm, this England,

This nurse, this teeming womb of royal kings…

____Footnotes____

[2] “Against the stream: C. S. Lewis and the Literary Scene,” Harry Blamires, 17.

[3] English translation of the Salisbury copy of the Magna Carta, with images.

[4] According to Wikipedia there are five. Moreover, Marsh’s Library in Dublin has no chains, but instead has cages for the readers (not unlike the rare book rooms I’ve visited).